What Widows Should Know About Grief and Cholesterol.

There’s a strange, quiet cruelty to grief: it doesn’t only live in your mind or your memories – it lives in your body, too. If you’re a widow reading this, you may already feel that truth. The ache that catches in your chest, the nights you can’t sleep, the appetite that disappears (or the comfort-eating that replaces it) aren’t just feelings.

Decades of research show that prolonged grief and the stress that often follows can change the chemistry of your body in ways that affect heart health, including your cholesterol and lipid levels. But knowledge is power. Understanding the link can help you make small, practical choices that protect your heart while you heal.

How stress from grief can alter lipids

When we experience major life stress-like the loss of a spouse—the body turns on survival systems meant for short-term danger: the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system. That means more stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline are released into your bloodstream. Over time, persistent activation of those systems changes how your liver and fat tissue handle cholesterol and triglycerides. In other words, chronic stress can push LDL (the “bad” cholesterol) and triglycerides up, and sometimes lower HDL (the “good” cholesterol). Several clinical reviews and observational studies link psychological stress with less favorable lipid profiles.

Beyond hormones, grief often brings behavioral changes that matter for lipids: poorer sleep, less movement, changes in diet, and social isolation. All of these make it easier for cholesterol and triglycerides to move in the wrong direction. A 2021 review that specifically examined the biology of widowhood describes how bereavement triggers inflammation and stress responses that contribute to cardiovascular risk — mechanisms

that can also influence lipid metabolism.

Is bereavement linked to heart risk – and where do lipids fit in?

You may have heard of the “widowhood effect” – the well-documented increase in mortality and heart events after the death of a spouse, especially in the first months. Researchers point to multiple causes: intense acute stress, changes in health behaviors, disrupted sleep, and biological changes, including inflammation and altered

lipid metabolism. While grief itself is emotionally defined, the downstream physiological effects overlap with established heart risk pathways, and lipids are part of that picture.

It’s important to be precise here: grief doesn’t magically “cause” high cholesterol in every person. But for many, the stress physiology and lifestyle shifts that accompany bereavement increase the chance their cholesterol and triglycerides will become less healthy, which, over time, raises cardiovascular risk.

What the studies actually say

- Reviews of stress and lipid profiles show consistent associations between chronic psychological stress and higher total cholesterol, LDL, and triglycerides in multiple populations. These are not magic one-to-one causes, but they are reproducible patterns across studies.

- Work on bereavement specifically finds that the early months of grief carry a spike in cardiovascular risk and that physiological systems (inflammation, autonomic changes, endocrine shifts) implicated in that risk can also affect lipids. A targeted review on widowhood biology lays out these mechanisms and the way they can intertwine.

- Studies of social isolation and stress reactions show that people who are socially disconnected respond to acute stress with larger cardiovascular and lipid-related responses, which matters because bereavement can amplify isolation. Oxford Academic

- Finally, research connecting psychiatric states (like PTSD and major depression) to lipid changes reinforces the general principle that intense, prolonged psychological distress is often accompanied by altered lipid profiles. While grief is not identical to these conditions, the biological overlap helps explain observed lipid shifts.

What this means for you – gentle, practical steps

If you’re newly widowed or have been carrying grief for a long time, you don’t have to feel helpless about this.

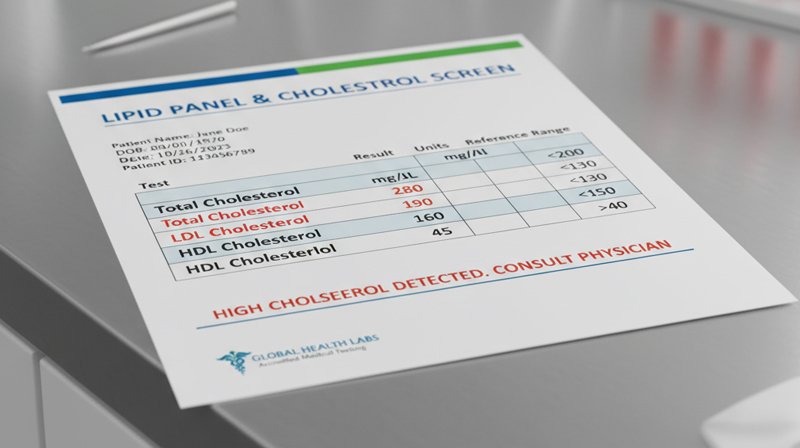

- Ask for a simple lipid panel. If you haven’t had your cholesterol checked since your spouse died, ask your doctor for a fasting lipid panel (or the kind your clinician prefers) and compare it to previous lab tests. Knowing is the first step toward healing. Since this is a medical test, you’ll want to discuss the results and any medication decisions with your clinician.

- Watch sleep and movement. Grief often steals sleep and motivation. Even gentle daily movement — short walks, light stretching, or the kinds of movement you enjoy – improves lipid metabolism and lowers stress hormones. Small wins matter.

- Mindful eating, not punishment. Grief can go two ways around food – undereating or overeating. Try to prioritize consuming whole foods, establishing regular meals, and hydrating by drinking pure, filtered water. If emotional eating is your refuge, be gentle with yourself and consider small substitutions (extra fruit, nuts, or balanced snacks) rather than strict rules.

- Connect, even in small ways. Social support buffers stress responses. A phone call, grief group, or meeting up with a neighbor for coffee can attenuate the physiological impact of isolation.

- Address the stress — for your heart and your soul. Practical stress care, like counseling, grief therapy, breathwork, meditation, yoga, or simply establishing consistent routines, can lower cortisol and inflammation, which in turn helps metabolic health.

- Work with your doctor. If your lipids are high, your clinician may suggest lifestyle measures and, depending on your overall risk, medication. Many people have successfully reduced their risk through lifestyle shifts alone.

Grief isn’t a life sentence for your heart

Losing a spouse reshapes the world. It reshapes the body, too — sometimes temporarily, sometimes in ways that need attention. The science tells us there’s a link between the stress of grief and changes in lipid and cardiovascular risk pathways, but it also tells us where to step in: nutritional interventions, sleep, movement, connection, medical checks, and compassionate self-care.

Your beloved did not get the chance to live more years, by your side, in good health. But you can do that for yourself. Isn’t that what they would want for you?